Dr Karem Roitman, OxfordAQA's keynote speaker at the TISSL Leadership Conference in Negombo, Sri Lanka, reflects on her presentation and the ways teachers can encourage skill development in the classroom.

There has been a lot of ink spilled on the skills that students need to become the leaders of the 21st century. We know they will need technical skills for jobs that don’t yet exist and to overcome challenges we can’t yet comprehend. We also know the importance of intangible skills – such as kindness, compassion and creativity – in creating an inclusive and beautiful future.

However, I think we need to spill a little bit more ink on how we develop these skills.

About the author

Dr Karem Roitman is an experienced education leader, an associate lecturer at the Open University in the UK and author of the Oxford International Curriculum’s Global Skills Project.

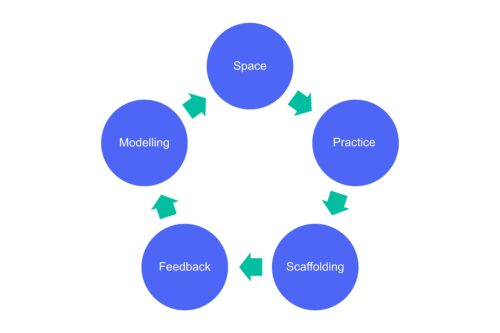

On 15 June I had the pleasure of presenting a skill development model to the brilliant leaders of Sri Lanka’s international schools at the 9th TISSL Conference. This model – the Pentagon of Skill Practice – is what I wish to share with you now.

We are always growing, working and continuing to learn and expand our skill set. That’s why I think the power of this model is that it applies to every aspect of our lives, not just within education.

As indicated by the model’s name, there are five key steps in learning and developing skills, which I will briefly summarise alongside a focus on creativity.

Creativity is a key aspect of our human wellbeing, yet it is also a skill that can be stifled or even forgotten in outdated, didactic teaching methods. So, how do we foster and protect creativity (and other skills) in our classrooms?

Space

Learning or developing a skill requires space in many forms – mental, emotional, time and physical space. We must make time for this process, even if this may mean taking time away from subject content.

Let’s look at creativity. Creating, coming up with new ideas, takes time. It takes emotional and physical space for trials and errors. It takes recovery time as we try and assess what we have created. Think about this in terms of a different skill: physical fitness. You will not get stronger by doing a 15-second workout once a month. You will, however, become fitter if you spend time every day moving and ensuring you take time to rest and recover.

It’s the same for our students. If we want them to develop a skill, we need to give them the space and time they need to do this.

Scaffolding

It’s easy to think of skills as complete wholes, but we need to consider their components to help students master them. If we simply tell our students to ‘be creative’ the goal is too broad and too intimidating. Instead, we need smaller steps.

For instance, take something that is already well-known and add something to it – such as adding a song or changing the goal of one character in a popular story. Or use the surroundings to spark imagination: take a walk and describe something you can see with 10 adjectives, and then 10 verbs that could apply to that object. While you can jump, dance or run on a mountain, or see, smell or touch one, you can slowly get more adventurous – you can scream at, speak or even recite to a mountain. Get silly. Have fun.

Practice

Skill development requires practice, especially given skills are context specific. So, while a student may be a creative writer, they may feel less confident approaching speaking or a maths problem in a creative way.

Our students need multiple contexts in which to practice being creative – have them imagine the lives of people at different times in history, attempt to find different ways of solving maths problems or challenge them to express themselves through different art forms. It can be as simple as having them devise a new way to greet you every morning or explain how to make a cup of tea.

Feedback

Feedback can be food or poison for skill development. A young person being creative can be encouraged to continue, expand their attempts and try something different. Or they can be embarrassed and discouraged from trying.

Our words, demeanour and attitudes have great power, which means we carry great responsibility when guiding students on nurturing different skills. It is our job as educators to find kind and helpful ways to encourage, support and inspire growth.

Modelling

Seeing others attempt, practice and master a skill is inspiring. I remember growing up watching the Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci and deciding that was what I wanted to be. I never became an Olympic gymnast, but she inspired me to spend countless hours moving, which ended up being great for my health.

Models give us ideas on how we might try to do things, but also the process of watching them try gives us encouragement to realise we can also try, not succeed, and still try again. This is one of the most important roles teachers play. We model skill learning, showing our students every day how we practice our skills – by trying new things, working to communicate with them, listening attentively, assessing information critically and, above all, being kind to ourselves in the process.